Imagine the siege of Amsterdam!

Imagine the siege of Amsterdam!

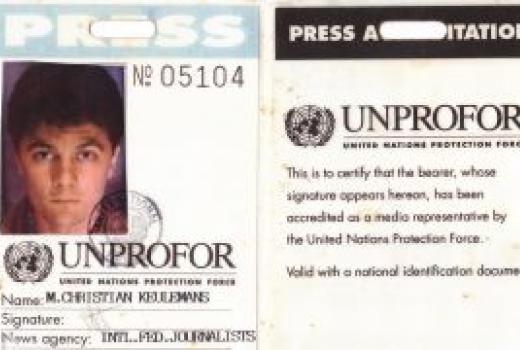

Chris Keulemans, writer and cultural manager from Amsterdam remembers his visits to Sarajevo under siege.

When did you arrive to Sarajevo and how much time have you spent there during the war 1992-1995?

My first visit was in June of 1994, the second in November of the same year. Both visits lasted a week. After Dayton, I kept returning almost every year.

Can you describe your typical working day in the besieged city?

Hospitality was everywhere. By the time I arrived (after having been active in supporting Bosnia’s independent arts and media from Amsterdam since 1992, and after having written a short novel in which I imagined Amsterdam under siege – such a naïve attempt!) the terrible first two winters were over. During my two wartime visits, there was a ceasefire, so it was relatively safe to walk the streets. People took care of me wherever I went. On my very first night, a beautiful summer evening, I was welcomed by friends seated around a sober, but elegantly arranged dinner table. My greatest discovery that night: kajmak.

Chris Keulemans (Tunis, 1960) is a writer and journalist based in Amsterdam. He visited Sarajevo during the siege twice in 1994 and many times after. His articles about the city under siege were published in Dutch weekly De Groene Amsterdammer. At the time, he was involved in setting up Press Now, a Dutch campaign to support independent media in the Balkans. His book of essays about the war was published in Bosnian by Dani in 1999, under the title ‘Od zapada prema istoku’. Currently, he is setting up a new arts centre in Amsterdam, de Tolhuistuin.

I stayed first at a pension close to the Koševo hospital, later at the home of a friends’ mother. These people took absolute care that I did not lack anything. Along the way, there was always coffee, very often orange juice, burek of course, and people were proud to introduce me to the smell and taste of cevapcici.

My days were not that long. I got up early, cleaned and brushed my teeth with the available water, walked from appointment to appointment, and apart from a few late nights at Obala, mostly went to bed early, completely exhausted – mentally, because of the sheer and utter seriousness of the place.

What was the most horrific experience from besieged Sarajevo?

Personally, I was lucky not to witness any shelling. I was not and am not a real war reporter. Not even a real journalist. I wrote and published because I felt the world should not forget about Sarajevo – by 1994, the world’s attention was moving elsewhere. And my articles and essays were mostly about what I understand – art, literature, media – because I felt these were the only subjects I could hope to cover seriously, in a city where everything defied my understanding.

The violence? I sensed it, but hardly witnessed it. In the evening, standing on the balcony of the house where I stayed, I heard distant gunfire. Once, Mehmed Husic, then editor of the Oslobedjenje press agency, led me to a corner of their building. Through the window, I saw a Serb sniper some 50 yards away. That was my moment of heroism… Infinitely more serious was the moment during an interview with Zdravko Grebo at Radio Zid, when news came in of a grenade, that had maimed seven children playing just across from the state tv building – Grebo hurled his pack of cigarettes across the studio, interrupted the music and cursed the news out into the ether. A moment of deep frustration about the helplessness, the exhaustion, the sorrow.

Infinitely more serious was the moment during an interview with Zdravko Grebo at Radio Zid, when news came in of a grenade, that had maimed seven children playing just across from the state tv building – Grebo hurled his pack of cigarettes across the studio, interrupted the music and cursed the news out into the ether. A moment of deep frustration about the helplessness, the exhaustion, the sorrow.

Personally, one heartbreaking experience that I will remember is visiting Nermina Kurspahic, the writer, sentenced to staying at home by her illness, who sat down patiently to tell me about the novel with the beautiful title Hiatus, which she had written that winter.

What was the most positive, or fun detail that you remember from Sarajevo during wartime?

Imagine me, inexperienced, not sure about what to expect, very solemn about witnessing the world’s saddest place at the time, modest and shy in the face of something so horrific, being invited to the MESS office just days after my arrival, when it happened to be the night of Bajram, and director Haris Pasovic and actor Velibor Topic invited me to sit down with them, opened a bottle of whiskey and started telling me jokes and surreal stories into the night. A bizarre scene, a scene of friendship, the last thing I had expected.

Have you made friends with colleagues journalists and local people who have assisted you during your work in besieged Sarajevo?

Yes. The people I met immediately understood, of course, that I was an amateur reporter at best. Although I was obviously serious about my writing, it was always a sideline to projects of support and cooperation which would continue after my stay. Especially after I started returning, people recognized that I might not be an award-winning journalist, but at least I wasn’t a frontline tourist either. So yes, I am proud to regard very different people like Aida Kalender, Haris Pasovic, Nihad and Sead Kresevljakovic, Boro Kontic, Senad Pecanin, Emir Suljagic, Zijo Gafic and many others as friends I love and respect, even when I don’t see them as much as I would like to.

Have you ever been in situation to apply self censorship on your stories from Sarajevo? Can you describe this situation?

No. The only reason to modify stories might be to protect the dignity of the people I spoke to. This was never a problem. Most of them had dignity in abundance. The shame lay in the situation that was forced upon them.

In my specific situation, when writing about the independent media and their editors, I had reason to emphasize their courage and professionalism and downplay my possible doubts – decisions about possible funding from the Netherlands could partly be influenced by my articles, and I saw no reason to add more obstacles to an already impossible situation. Was this a form of selfcensorship? I don’t think so. Whatever my superficial impressions (as I did not speak the language and was not able to judge the content) about the level and political choices of media such as Radio 99, Slobodna Bosna, Dani or Oslobodjenje, my admiration for their perseverance was true.

Do you think that reporting from besieged Sarajevo was objective?

Hard to judge. In general, most journalists must have shared my perspective. The obvious reality was that the city was surrounded by firepower, that civilians were targeted as a matter of routine, that the international community was fairly impotent in its attempts to protect Sarajevo and other cities in Bosnia. This means that much reporting had no option but to choose the side of the victims. Objective journalism is very often an illusion to begin with, in my opinion, and during the siege of Sarajevo most attempts by serious war reporters to give a general overview of the bigger picture must have often been tipped off-balance by the sheer despair they witnessed in the streets of this city.

The obvious reality was that the city was surrounded by firepower, that civilians were targeted as a matter of routine, that the international community was fairly impotent in its attempts to protect Sarajevo and other cities in Bosnia. This means that much reporting had no option but to choose the side of the victims. Objective journalism is very often an illusion to begin with, in my opinion, and during the siege of Sarajevo most attempts by serious war reporters to give a general overview of the bigger picture must have often been tipped off-balance by the sheer despair they witnessed in the streets of this city.

What stays with me is how difficult the UN made it to remain objective. Entering the city was tiresome, the procedures were random and unpredictable. And whichever entry you took, it seemed like the UN screening in advance was even stricter than that at the Serb checkpoints into the city. The blue helmets seemed so fearful to remain neutral, that I personally became more subjective by the minute.

How do you see the role of the international media and the progress of the Bosnian war? Was media the key factor for the NATO intervention which actually stopped the war?

Whatever role the international media played in influencing the outcome of the war, they could only perform thanks to the neverending input from local Sarajevo journalists, writers, filmmakers, actors and citizens. If Sarajevo had shut up, the world would have forgotten about it. Intervention would not have happened. Srebrenica lacked that visible number of spokespersons.

If you have reported from other conflict (war) zones after 1995, could you compare your experiences from Sarajevo war-time to another war situation? Are there a similarities? And what are the main differences?

After Sarajevo I remained a faithful amateur journalist. As a friend of mine said, whenever there’s a crisis, you can be sure that Chris will be there – a year later. My interest is not in military action, it’s about the survival of cities and its people. When I later visited places like Beirut, Gaza and Ramallah, I was equally impressed by the energy and eloquence of the people who endured. They were trapped, too, and they also knew how to reach out and grab the world’s attention. The difference might be that they had witnessed decades of war and oppression. Sarajevo had not. In Sarajevo, the first thing that the city and its people shared with you was the shock, the sheer outrage about the sudden breach of civilization, of things being the way they were supposed to be, of being able to wash your hair with warm water, of skiing in the mountains surrounding the city instead of being shelled from above, of enjoying food, art and music as a matter of routine instead of having to conjure them out of thin air.