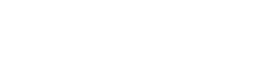

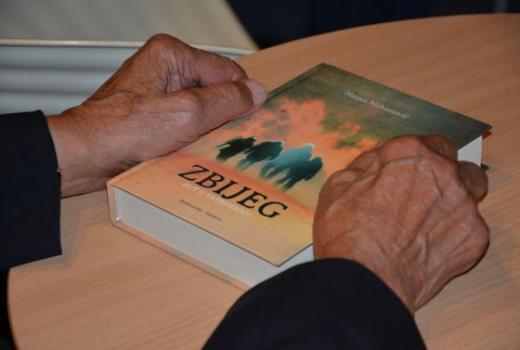

Book about Srebrenica by Hasan Nuhanović

Book about Srebrenica by Hasan Nuhanović

09/07/2015

Until 1992, Hasan Nuhanović, a boy from Vlasenica preparing to go to Sarajevo and study mechanical engineering, was aware of his talent for music. We learn about this from the first few pages of the book in front of us. And in it, unaware of what is coming, Nuhanović is playing music and singing a patriotic song.

As you finish the book, you arrive to the conclusion that Hasan Nuhanović – no longer a boy from Vlasenica, but a man from Srebrenica – also has a gift for writing. This adds another value to this book. In times burdened with events that are likely to remain contentious for quite some time to come, we should be grateful to anyone who decides to write their testimony seriously and conscientiously. And Nuhanović is one of those witnesses who know how to differentiate what they have seen from what they have heard or read. We thus have before us a witness we can refer to. When he speaks about something he has heard, Nuhanović cites a source. If his recollection is uncertain, he indicates that. And that is why Hasan Nuhanović is an example one should look up to.

He is at his most interesting and most precious when he speaks about what he has seen. A note: in addition to a gift for writing, there is also a gift for observing. Nuhanović is obviously very observant. There is an added symbolism to his observance combined with his poor eyesight, which he sometimes mentions in the book.

If a teacher was to ask a class to summarise the plot of the book in a single word, the answer could be: survival.

The imperative of survival is a double-edged sword. It stimulates what’s best in a human being, but also what’s worst. Nuhanović does not shy away from recalling both. And not just recalling: he digs through his own wounds. The Nobel Prize-winning writer Czesław Miłosz once wrote that memories were the part of our lives we can recount with no sense of shame. Hasan Nuhanović does not suppress the memories that make him feel ashamed and make him re-examine how great or how small a man he was in horrific circumstances. The magnificent scene, reminiscent of the great Ancient Greek tragedies, when Nuhanović fights his own father, is truly unforgettable. Nothing but snow and ice around them. It takes a great man to admit to such a scene and then write about it. And that is why those whom Nuhanović mentions by their moment of human weakness, theft of food or something like that, should not be upset by it. Nuhanović does not refer to them by name. To himself – yes. He does mention that he was a bit upset with his mother for giving him a smaller piece of bread than the one she cut for his brother.

This book contains examples of superb human qualities, but also some saddening examples of human weakness. If the latter were absent, had Nuhanović kept silent about that, the book would not have seemed credible. For all the great writing about detention camps – and Srebrenica was a detention camp – speaks about that. Those who have read Varlam Shalomov and his The Kalyma Tales cannot read Nuhanović without recalling this superb camp writing. Without any exaggeration, one can say… some of the brilliant tales from Nuhanović’s book could be published as separate stories. Superb literature. Of the Shalomov kind!

The book has its characters and the narrator is one of them. He does not take the position of the ultimate judge. Nuhanović is not the kind of witness who is soft on himself and harsh on others. One of the best scenes of self-irony is when he prepares to give a statement to a foreign journalist. His glasses are glued together, he prepared a few short sentences in English, and he suddenly notices through the haze of his scratched lenses that the journalist is looking through him rather than at him, her eyes drawn to a person standing behind him. The person is Naser Orić, about twice Hasan’s size. There are many different ways of looking at characters and events. And this very scene should be one of Orić’s portraits and one of Nuhanović’s self-portraits. At that, nothing should be explicated or concluded; one should just look at this striking picture. And there are many such pictures in this book. Nuhanović has a great talent, to describe the situation in such a way so that you can actually see it. You just see it! For example: the night when Nuhanović returns to his refugee home from an evening out in Srebrenica and finds his mother awake, and his father and brother sound asleep. He asks his mother if she believes in God. The reader feels and hears every sound that the darkness of this night in Srebrenica produced. The scene is such that it makes readers ask themselves the same question Hasan Nuhanović asked his mother. Only the greatest literature does that. Another unforgettable scene is that when the characters seem to be hanging between the skies and an abyss. A son is pulling his huge mother. And Hasan wants to kill the son, since he thinks that the other boy would kill his mother if given the chance. The scene is both grotesque and moving. One of those ‘blood-curling’ scenes.

Another unforgettable scene is when Huhanović and his uncle play chess as the criminals’ planes fly above them. But this time the planes are not bombarding them, they are en route to bombard Žepa. This gives them the reason to sigh with relief. The uncle utters “Yah”, a well-known sigh typical of the minimalist Bosnian communication. Nuhanović – and this is a talent not bestowed upon all writers – knows how to make his characters speak. He knows how to bring them to life with the sentences they uttered and he remembered. And this is not easy. Every writer knows how hard this is. Whatever we hear takes only a few minutes to blend into arbitrary memory and improvisation. As you read his dialogues, you feel as if listening to a taped recording. Many of those whose sentences Huhanović remembered and recorded are no longer alive. That is what makes this book even more valuable. It makes the dead – the killed – speak. This is one of the most noble imperatives of writing testimonials. Nuhanović responded to this imperative in a way that is deserving of our admiration and respect.

Translation: Amira Sadiković

Supported by The British Embassy in Sarajevo